Don't Get Better. Be Less Bad.

If you always rely on what you learnt and “know” worked 5 years ago, soon you will be a dinosaur in your thinking. Slow and massive, your lumbering decisions can wreak havoc on those underfoot.

Unforced errors are scrutinised in sport. Top level tennis players keep a count of unforced errors. An errant serve. A missed easy return. A double fault. Their coaches drill down on these errors and work to eliminate them.

Why?

Because they know the about German mathematics.

To be more precise, the know the distilled wisdom of German mathematician Carl Jacobi who said “Invert, always, invert.”

Instead of focusing on getting better, they focus on the inverse.

Being less bad.

Once the focus is flipped new avenues of better performance and decision making are opened.

Medics are not trained to think like this. Yet the fallout of our unforced errors are can be life-changing for patients. We are trained to analyse why something works and pay little to no attention on how to be less bad.

Let’s address this.

Complex decision making requires the analysis, assessment and then synthesis of a solution. In medicine there are granular scientific facts, like a CT scan and blood test results, but also fuzzy, difficult to quantify human factors like fatigue, temperament and experience. We often fall to “gut instinct” when making decisions, relying that this instinct is based upon an unseen but unconsciously analysed bank of memorised information and remembered experience.

The problem with this is that in the current shifting sands of rapidly advancing science and data, what worked in the past may not be the best solution today. If you always rely on what you learnt and “know” worked 5 years ago, soon you will be a dinosaur in your thinking. Slow and massive, your lumbering decisions can wreak havoc on those underfoot. Not only that, you may just walk yourself off a cliff with your myopic vision and end up in front of a judge.

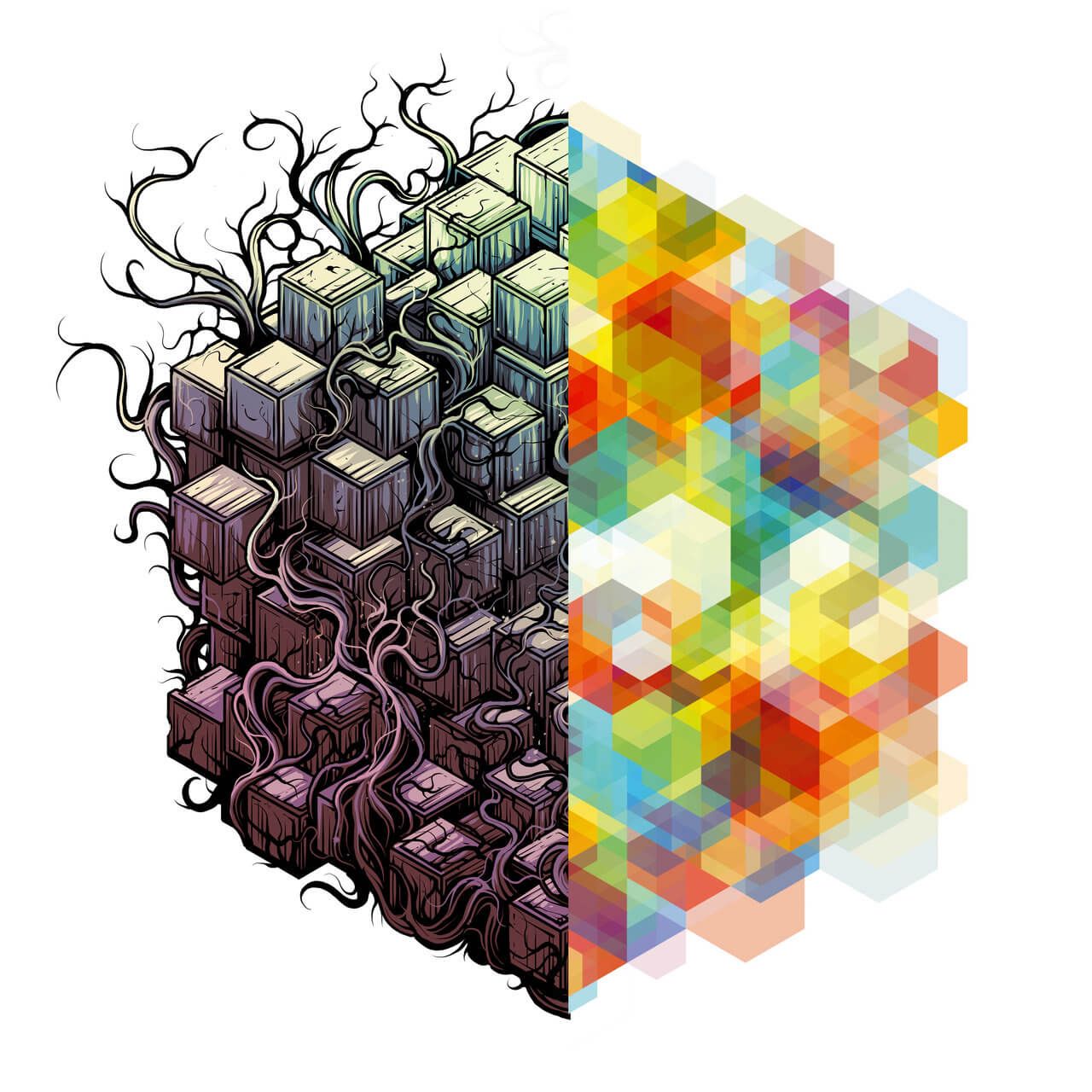

However there is a set of tools that will keep your thinking sprightly and sharp, irrespective of the problem. What can be achieved is a decision making model that is Antifragile.

As you know, something that is fragile will break easily. This is the under-equipped medic who is out of their depth and makes poor decisions. Something that is robust will withstand pressure and continue the same with the passage of time. The problem for the robust medic is the angle and intensity of that pressure will change with time. At some point their robustness will fail and they while display their fragility. The antifragile medic will get better with time. Each decision they make, irrespective of outcome, will improve their decision making models. This is what it means to be antifragile. You welcome difficult decisions and stresses as you know the models you have in place will arm you to make good decisions and most importantly, improve.

Forever there will be those who will back their decisions based upon previous success. There will also be those long enough in the tooth to say “I can trust my gut” and that “bias is there for a reason”. But you don’t have to look far outside medicine to see those hyper-successful decision makers who concede to the importance of antifragile thinking and mental models:

Charlie Munger - Vice Chairman Berkshire Hathaway, billionaire

Richard Feynman - Physicist, Nobel Prize Winner

There is also no harm in developing a system of mental models to check your gut instinct against. More so, if they both reach the same conclusion you are more assured in your decision. If they differ you have afforded yourself an opportunity to pause and ask why?

I was operating years ago as a trainee performing spinal surgery. The surgery was not complex and involved removing a disc from someones lower spine. I thought I had removed the disc but as pattern recognition kicked in i new something was wrong. Slowly it dawned on me that what I had cut was the nerve travelling to the patient’s leg and not the disc. They had a rare variation, where instead of where normally one nerve travels, they had two. I had identified the nerve and assumed the next thing I saw was a disc.

What happened next was a wave of nausea, sweating and racing thoughts. Will they be disabled? Will they have a paralysed foot? Can i finish this operation? I was aware enough to stop and ask my trainer to scrub in. They noted the problem and finished the case. The patient was fine. Better than fine actually, they no longer had any leg pain which was the reason they had undergone the operation. Sometimes surgery is like that. I informed the patient of events as my duty nevertheless.

The next case I had to do was the same operation on a different patient. Seeing I was rattled my trainer told me “back on the horse for the next case”. I performed the next case without problem and have thought about that day ever since.

What my trainer exposed, and then dismantled, was the Gambler’s Fallacy. Just because the roulette wheel hits red, doesn’t mean the next spin will be red or black, or however you think those events are linked. The Gambler’s Fallacy is to believe that two non-causally linked events are linked, and then make a decision upon this erroneous belief. If i had believed that because I had a complication on my first case, I would have one in my next case, I would have invited unforced errors. My recall bias and poor innate grasp of causality would have made it more likely for me to make errors.

This is system 1 thinking as Daniel Kahneman states.

System 2 allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it, including complex computations. The operations of System 2 are often associated with the subjective experience of agency, choice, and concentration.

System 1 is good for gross, everyday decision making that requires minimal energy; but not for complex, nuanced situations that decision makers face each day.

A softer example is when I have seen colleagues being angry or sharp with people trying to refer patients. I often think I wouldn’t act like that and have generalised that they are difficult people to speak to work with. However when I have been short with people I justify my behaviour because I’m tired, hungry or am just in a bad mood.

This is the Fundamental Attribution bias. I’m more likely to attribute someone else’s behaviour to their character and my own to circumstance. Once I see this error I no longer carry my preconceptions into future interactions with my colleagues, which would also lead to unforced errors in day to day interactions.

So how can we reduce unforced error and be “less bad”?

Below is a step by step system to form a mental model lattice work.

Step 1 - Find the Cause

Subjectivity and bias obscure the real cause of problems, be it a disease or work place conflict. There are 3 steps to finding the cause.

Step 1a - First Principles

To overcome conventional wisdom and outdated thinking revert to 1st principles. This means having a strong understanding of the natural history of disease and anatomy as a surgeon. This is assessed in neurosurgery by the FRCS.

Step 1b - Root Cause Analysis

Complex problems have "obvious" initial causes. This is the proximal cause. However to tackle the problem you need the root cause.

e.g. the bleeding wouldn't stop during surgery.

Asking "why" at least 5 times will lead you to the root cause.

Why? `The correct haemostatic agents weren't available (proximal)

Why? It wasn't mentioned at the brief

Why? The surgeon didn't mention it

Why? The surgeon is a trainee and didn't discuss it with their consultant

Why? The consultant doesn't like being asked questions (root)

Step 1c - Seek the Third Story

When conflict arises between you and a colleague or patient there are 2 stories.

Neither are "true" or correct.

To be objective formulate the 3rd story.

What would an objective observer conclude based upon both views? Step 2 Filter

Nature has hard-wired us for bias enabling us to make quick general assumptions as a survival benefit.

However this leads to bias and tribalism. Being aware of the common biases allows us to filter them out.

Step 2 Remove Bias

Bias in inherent in our decision making and is the greatest cause of unforced errors and must be overcome.

Step 2a Break the Frame

How information is delivered effects our decision. 10% of death vs 90% survival of an operation paint very different pictures. This is because we are risk averse.

This is the framing effect.

Look for the frame when information is given to you.

Step 2b Drop the Anchor

Along with the framing effect comes anchoring.

You will give a disproportionate amount of value to the first piece of information you are given.

This is how an auction works with its starting price.

Detach from the first line of the story.

Step 2c What You See is All There Is (WYSIATI)

We assume what we see is more common that it actually is.

This is why we x10 the perceived incidence of violent death due to news articles vs x1/1000 the more common causes such as stroke/MI/diabetes.

Ask - what am I not seeing?

Step 2d Burst The Bubble

Online search algorithms will show you articles you want to see. This will keep your thinking contained with a bubble.

This is known as a Filter Bubble.

Burst the bubble by using other mediums. Internet vs textbooks

Step 2e Avoid the Echo Chamber

Group opinion+filter bubble=echo chamber. If you ask the same people in a group for opinions over time the same answer will be repeated back to you.

Actively seek opinions from novel sources.

Step 2f Fundamental Attribution Bias

See someone angry when taking a referral = difficult colleague to work with. I get angry taking a referral = i'm tired/hungry/in a bad mood.

We attribute others behaviour to character and our own to circumstance.

Solution-see MRI 👇🏽

Step 2g Watch out for Backfire

If you disprove someone's beliefs they are likely to double down initially, even in the face of clear evidence.

This is The Backfire Effect.

Take the first reaction with a pinch of salt when disproving other's beliefs.

Step 3 Synthesise

Now you have objectively found the root cause and filtered out bias, the next step is to synthesise a solution.

Step 3a Assume Nothing

From our example in 1b the root cause may be a difficult consultant, but you need to "derisk" your assumptions from proximal to root.

Assess the answers to each of your whys in turn. You may find one assumption untrue, if not, continue to the root cause.

Step 3b Wield Razors

Ockham's razor states the simplest explanation is usually the correct one.

Assess your solution.

Is it overly complex?

Is any part unnecessary?

Can any steps be cut away?

Step 3c MRI

Now you have an explanation/conclusion.

If it involves human factors apply Hanlon's razor or The Most Reasonable Interpretation.

Do not attribute to malice that which can be explained by ignorance.

Step 4 Pre-test

Now you have an objective root cause, removed of bias and have synthesised a solution removed of unforced errors

The next step is to counter your own solution.

Step 4a Devil's Advocate

The Devil's Advocate was a position in the church to argue why someone should not become a saint.

Ask - how would someone argue that your solution is flawed? Come up with more than one argument.

Step 4b Think Grey

Now you have counter arguments to your solution.

Weigh them all against each other.

This will be difficult due to cognitive dissonance so lean into that discomfort.

Avoid black and white binary thinking, aim for grey.

Step 4c Don't Trust Your Gut

Intuition has its place, but work in a field long enough and that which you at first deliberately thought about eventually gets shipped to autopilot.

System 2 content becomes System 1 where bias and error thrive in complexity.

Check your gut.

Step 5 Real World Test

You now have done everything you can to remove unforced errors when faced with complex decisions and to be less bad.

Test your decision by its application.

Step 6 Seek Feedback

Were your correct or incorrect in your decision?

Remember - There is no failure. Only feedback.

Step 7 Spin the Flywheel

If you were incorrect, input your new knowledge into this framework and refine your decision making ad infinitum to a razor's edge.

If you follow this system you will reduce unforced errors in your decision making.

This may seem like a slow and detailed process, but that is exactly how you should proceed when faced with complex decisions.

I hope this article was helpful to you and you enjoyed reading it.

If you want to receive an infographic summarising this model to use, sign up to my newsletter and I'll send it out soon.

I also deliver a weekly dose of my reflections in my newsletter. If you'd like to get one every Sunday for free, you can subscribe below and I'll send them your way.

If you want to get in touch, feel free to follow and DM me on Twitter @adi_kumar1.